I get asked this question a lot when I teach courses in the history of medicine or the history of science. Even more commonly, people tell me they “know” what plague doctors looked like: they had a mask with a long beak, goggles, gloves and a garment that covered them from chin to ankles. Indeed, the 12-year-old son of some friends of mine just dressed up as a plague doctor for Halloween in precisely this costume. But doubts about the historical accuracy of the plague mask have nagged at me for a while. If it was so common, why didn’t I ever run across mentions of this costume in historical sources or in histories of the plague written by academic historians? A Google search on “plague doctor” turns up an enormous number of images of men in beaked masks and black cloaks, and numerous sites that assert as historical fact that this is what doctors wore during plague epidemics. Let me give you a couple of my favorite examples:

There is a doctor character in the enormously popular video game Assassin’s Creed who wears a plague mask. I pulled this picture from the Assassin’s Creed Wiki, which explains that,

“To protect themselves from this pandemic, doctors dressed in a long black cloak covered with a coating of wax, along with a very primitive beak-shaped plague mask, although not all doctors chose to wear it. Within this Medico Della Peste mask, there were usually flower petals, burning incense or aromatic herbs to rid of bad smells, since it was believed that disease was transmitted through “bad air.” The eyes of the mask were also made out of glass, as it was believed that sicknesses could be caught through face-to-face contact with patients, or by touching infected objects.”

My other favorite was this fantastically creepy video on YouTube: The Plague Doctor. Set in 17th-century London, a sick gravedigger visits a plague doctor, only to be told he is dying and that the doctor will not treat him. In anger, he slashes the doctor’s protective glove, thus infecting him with the deadly plague.

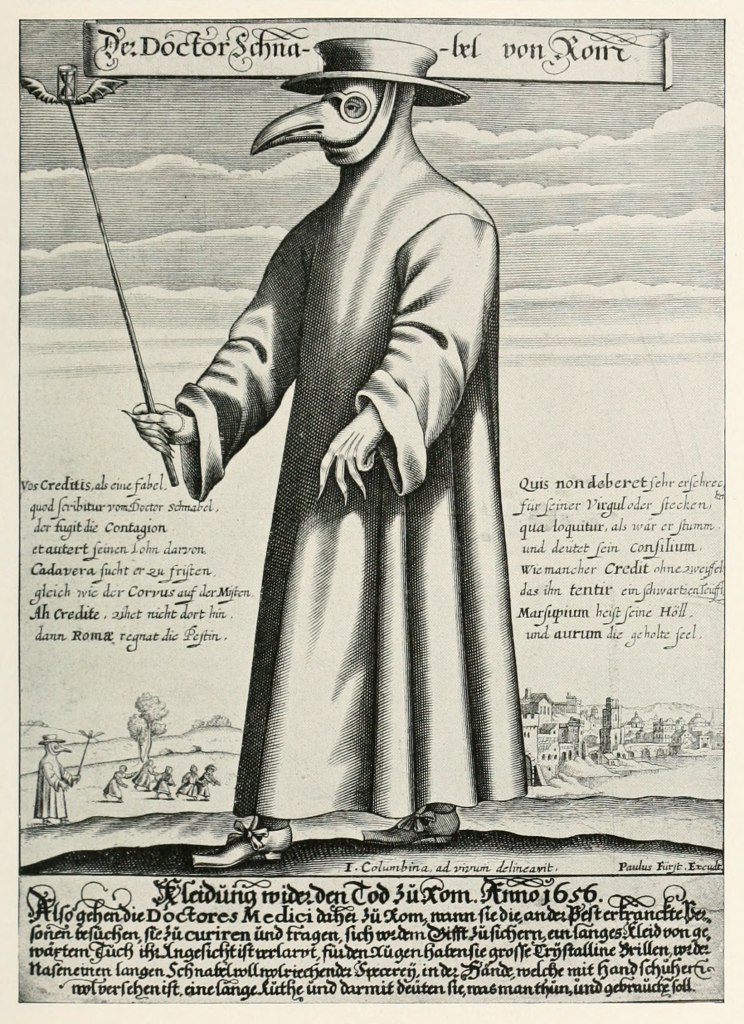

My problem with these representations is that the only even remotely contemporary image I can find of a plague doctor in such a get up is this one, from 1656:

This image was originally a single-sheet broadside, produced by the German engraver Paul Fürst of Nuremberg. The reproduction that appears all over the internet (generally without attribution) is from Eugen Holländer’s Die Karikatur und Satire in der Medizin, 2nd ed. (Stuttgart, 1921). This entire book is available on-line here. The first thing I would note is that this is VERY late in the history of the plague. The very last plague epidemics in Europe were in the early eighteenth century. The second thing is that this is a SATIRE. As this seems to be the main primary source for what plague doctors wore and what they did, I’d like to look at it in detail. The title is “Der Doctor Schnabel von Rom” (Dr. Beak from Rome). The caption at the bottom is in German. I’ll give the original (for those who can read German but not the old-fashioned Gothic lettering) and my translation. (Corrections and suggestions are more than welcome!)

Kleidung wider den Tod zu Rom. Anno 1656. Also gehen die Doctores Medici daher zu Rom, wann sie die an der Pest erkranckte personen besuchen, sie zu curiren und tragen, sich widerm Gifft zu sichern, ein langes kleid von gewäxtem Tüch ihr Angesicht ist verlarvt, für den Augen haben sie grosse Crÿstalline Brillen, wider Nasen einen langen Schnabel mit wolriechender Specereÿ, in der Hände, welche mit Handschüher wol versehen ist, eine lange Rüthe und darmit deüten sie, was man thun, und gebraüchen sol.

Clothing to ward off death in Rome, 1656. The doctors of medicine in Rome go about thus, when they visit people sick with the plague in order to take care of them. And they wear, to protect themselves from poison [infection], a long robe made of waxed cloth. Their face is wrapped up; in front of their eyes they have large crystal glasses; over their nose they have a long beak filled with good-smelling spices; in their hands, which are protected by gloves, they carry a long rod and with this they indicate what people should do and what [medicines] they should use.

This sounds exactly like the description of the plague doctor’s attire from the Assassin’s Creed Wiki (and numerous other websites). That seems pretty conclusive, right? It’s a primary source document, so here we have a seventeenth-century person’s description of plague doctors he actually observed. Or do we? Here’s what gives me pause. The verses on either side of the figure are what mark the broadside as satirical (also calling the figure “Dr. Beak”). These verses are in a mixture of Latin and German. Again, I will include them here in both the original languages and my translation. I am not nearly good enough to render them into rhymed English, but I’ve tried to capture the sense of the originals. (Again, suggestions and corrections are welcome!)

Vos Creditis, als eine fabel

quod scribitur vom Doctor Schnabel

der fugit die Contagion

et aufert seinen Lohn darvon

Cadavera sucht er zu fristen

Gleich wie der Corvus auf der Misten

Ah Credite, sihet nicht dort hin

Dann Romae regnat die Pestin.

Quis non deberet sehr erschrecken

für seiner Virgul oder stecken

qua loquitur als wär er stumm

und deutet sein consilium.

Wie mancher Credit ohne zweiffel

das ihn tentir ein schwartzen teuffl

Marsupium heist seine Höll

und aurum die geholte seel.

You believe it is a fable

What is written about Dr. Beak

Who flees the contagion

And snatches his wage from it

He seeks cadavers to eke out a living

Just like the raven on the dung heap

Oh believe, don’t look away

For the plague rules Rome.

Who would not be very frightened

Before his little rod or stick

By which means he speaks as though he were mute, and indicates his decision

So many a one believes without doubt

That he is touched by a black devil

His hell is called “purse”

And the souls he fetches are gold.

The verses begin by marking the plague doctor as an UNFAMILIAR sight. You may believe what I’m about to tell you is just a fable, the author begins. In other words, this is NOT how doctors in Germany dress. This is a strange, Italian custom. And then he goes on to lampoon the plague doctors of Rome. They protect themselves from contagion, but they profit from it. They seek out the dying to get money from them, just like ravens (or crows) scavenging in a pile of shit. Like the Devil, who goes among the dying, seeking souls he can drag into hell, Dr. Beak goes among the dying, seeking gold coins to put in his purse. This satire certainly resonates with a good bit of contemporary critique of doctors as rapacious and greedy. But I wonder, was the comparison of the plague doctor to a raven inspired by the resemblance of the plague mask to a bird’s beak, or was it the other way around? Was the mask in this image exaggerated to look beak-like because of the comparison to an avian scavenger? Note that the fingers on the gloves are elongated and pointed, like the talons of a bird. There is nothing in either the poem or the passage below the image to indicate why this might be medically efficacious. Finally, at the end of the rod is an hour glass with wings, a visual symbol of the saying “tempus fugit” (time flies) (originally from Virgil’s Georgics). Surely no plague doctor ever literally carried such a device! Rather, the emblem suggests that the doctor is the harbinger of death rather than a savior. All things considered, I’m left unconvinced that this is a literal description of the costume of a plague doctor. And I’ve yet to find evidence that would convince me.

Why does it matter whether or not plague doctors dressed up like ghoulish carrion birds? One problem I have with the popularity of the figure of the plague doctor is that it erases the very real contributions of women to medical practice generally, and to the care of plague victims specifically. Numerous historians of medicine (I’m thinking here of Monica Green, Katherine Park, Margaret Pelling, Mary Fissell, Deborah Harkness and Gianna Pomata among others) have documented the presence of female healers in medieval and early modern Europe. These women did not function exclusively as midwives (although all midwives were women). Rather, they performed a wide range of medical services and treated men, women and children for all kinds of illnesses and injuries. A substantial amount of medical care in medieval and early modern Europe was provided by women, and yet women do not figure in any popular representations of the plague, except perhaps as victims. In 17th-century England, where the creepy video is ostensibly set, the people who sought out plague victims and determined the cause of death were women called “searchers.” They did the dangerous work of examining dead bodies, not the doctors. (For more on the searchers, see here.) Indeed, there were repeated accusations in early modern London that “doctors,” that is, men with medical degrees who were members of the Royal Society of Physicians, fled London for their country houses whenever a plague epidemic threatened. These same doctors then complained bitterly about female “empirics” cutting into their business by treating plague victims.

So, what’s my answer to the question? Did plague doctors actually wear those masks? I still don’t know. But I find the question of when and why the figure of the masked plague doctor became iconic in representations of plague to be an increasingly intriguing one.

UPDATE: Great video on the plague and plague doctors by Dr. Lindsey Fitzharris.

Great article. I’ve tackled this subject on The Chirurgeon’s Apprentice before, and will be releasing a YouTube video this week on the very subject! I agree that it’s difficult to know how ubiquitous the mask was… seems unlikely many doctors actually wore it.

LikeLike

Yes, I’m looking forward to that YouTube video. Will include a link in this post as soon as it’s out!

LikeLike

At last, someone attempting to deconstruct the trope! What I find fascinating is not so much whether anyone ever wore this costume, but why the internet has picked up the image and run with it. The plague doctor, like the vampire, has spread everywhere from one or two early modern references!

LikeLike

I am looking for the poster from Marseille with the 4 thieves vinigar posted on it. Is this a myth poster? I thought the plague doctor was it.

LikeLike

There are more images at the Wikipedia Commons. Most seem to point to a 1720 plague epidemy in Marseille. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Plague_doctors

LikeLike

Hello, Dr. Crowther; Thank you for the article. I used your Doctor Schnabel translation here: https://dv8s.com/blogs/news/new-plague-doctor-t-shirts-tanks-sweatshirts-and-hoodies. I hope that is OK. If you would like the translation removed, or the citation changed in any way, you need only ask. Thanks!

LikeLike

No problem! Cool shirts!

LikeLike

Thank you for this! I too was sceptical of the bird-face mask. I assume that the originals were rather more shapeless and gasmasky, and only vaguely resembled a bird’s face. After all, why would the actual physicians wear literal animal masks when working with suffering people?

But the clear association with the poor maligned corvid is clear and nonetheless interesting, as is this German perception of Italian physicians.

LikeLike

A variant is suggested to the transcription of line 7:

zihet (instead of sihet) would translate as travel, hence “do not travel there, because in Rome the Plague rules.”

Interesting, that the Plague (die Pestin) is in the female gender and also, that the poem is addressed to “the believer” (Lat. creditus).

While the upper, illustrated part is indeed a satire, the commentary in “Kleider wider den Tod” seems quite factual. While reg smell of aromatic herbs in the beak may not have done much, the herbs themselves could have filtered the air for Doctor Schnabel.

Dr Tom M., Ottawa, Canada

LikeLike

A very interesting sceptical take on the image but at least the use of a mask filled with herbs and spices is confirmed by Defoe in his Journal of the Plague Year. Near the end he lists the herbs and spices used by his favourite doctor informant who believed they kept him safe. Of course Defoe’s work is not as factual as he makes out and he was a journalist……and he may have seen the image himself since he clearly did some research. And you’re certainly right that it was a satirical print.

LikeLike