This page provides some background information on medicine in Europe in the Middle Ages and early modern periods (roughly 1000 to 1750). It is not intended to be comprehensive – the subject of medieval and Renaissance medicine is simply too large for that! Rather, it is intended to provide context for the more specialized topics that follow. I will address three topics in this page:

- The rise of universities and medical schools in medieval Europe.

- The development of the concept of temperaments.

- The relationship between medicine and Christianity.

I. UNIVERSITIES AND TRANSLATIONS

When universities developed in Europe in the 12th century, medicine was one of the subjects taught, and the medical school curriculum was based heavily on the works of Greek and Arabic physicians. These works were translated, mostly from Arabic, between the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Two of the most important translators were Constantine the African (died before 1098/1099) and Gerard of Cremona (ca. 1114–1187). Constantine was an Islamic doctor who spent time in North Africa and Italy. In the Italian city of Salerno (which was a renowned center of medical education even before the development of universities) he attracted the support and patronage of the local Lombard and Norman rulers (including some prominent noblewomen). Because of this support, Constantine was able to translate numerous medical works from Arabic into Latin. He eventually converted to Christianity, became a Benedictine monk, and lived out his life in a monastery in Monte Cassino. Gerard was an Italian scholar who traveled to Toledo, learned Arabic, and translated numerous scientific and medical works from Arabic into Latin. We have encountered Gerard’s translations before as he translated Ptolemy’s Almagest. He translated several medical books by both Greek and Arabic authors. His most important medical translation was the Canon by the Islamic physician Ibn Sina (known in Europe as Avicenna). This book became the standard teaching text in European medical texts until the seventeenth century.

II. TEMPERAMENTS

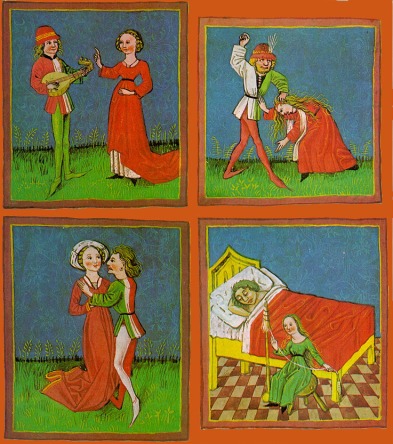

European medicine in the medieval and early modern period was firmly based on the theory of the four humors, which originated with the Greek physician Hippocrates, and was elaborated by the Roman physician Galen, and by physicians in the Islamic world. One change to the theory of the humors in the late Antique period (i.e. around the 6th century AD) was the development of the concept of the “temperaments” or “constitutions.” This was the idea that, although each person had his or her unique balance of the humors, everyone fell into a few broad categories. A person’s balance of the four humors – blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile – was referred to as their “temperament” or their “constitution.” (I will use these terms interchangeably in what follows.) While everyone’s temperament was unique – no two people are exactly identical – there were four broad categories of temperaments. Someone who had a preponderance of blood in his or her constitution was “sanguine.” This term derives from the Latin word for blood, sanguis. Someone who had more phlegm than the other four humors was phlegmatic. Someone who had more black bile than the other three humors was melancholic. This term derives from the Greek work for black bile, melancholia. Finally, someone who had more of the humor yellow bile than the other three humors was choleric. This term derives from the Greek word for yellow bile, cholera. These were the four simple temperaments. It was also possible to have a mixed temperament, which meant you had a preponderance of two of the four humors, but I will concentrate on the simple temperaments, since they were the most frequently depicted by artists and described by medical writers.

A person’s temperament determined their physical makeup and what diseases they were most prone to. It also determined their personality. To illustrate the ways in which physical and personality traits were intertwined in the notion of the temperament, I have drawn descriptions of the four temperaments from a sixteenth-century English medical book, Thomas Elyot’s Castel of Helth (1541). Elyot’s descriptions of each type are consistent with descriptions in other medieval and early modern medical texts.

Elyot lists the characteristics of each of the four basic temperaments:

The sanguine person is:

- Fleshy, but not fat

- Physically vigorous

- Pink and white complexion

- Optimistic, cheerful

- Easily roused – anger, affection

- Intelligent

The choleric person is:

- Lean

- Physically vigorous

- Complexion ruddy or sallow

- Mentally sharp and quick-witted

- Hardy and aggressive

- Prone to fight

- Easily angered

The phlegmatic person is:

- Fat and soft body

- Pale

- Slow – physically and mentally

- Stoical – or hard to rouse

- Dull-witted, not smart

- Cowardly

The melancholy person is:

- Lean

- Complexion pale

- Anxious, fearful

- Stubborn in opinions

- Brooding – bears grudges

- Timorous and fearful

- Morose

- Seldom laughs

You might note some patterns. Those dominated by the wet humors (blood and phlegm) are fleshier than those dominated by the dry humors (yellow and black bile), who tend to be lean. And those dominated by the hot humors (blood and yellow bile) tend to be more vigorous, both physically and mentally. They are also more courageous.

Each different temperament was vulnerable to different diseases. Someone dominated by the humor black bile would be prone to diseases caused by excess of black bile. If you (or your physician) knew what your basic constitution was, you could take steps to prevent yourself from getting the diseases you were most prone to by eating foods that tended to counteract your natural temperament, as well as by getting the right kind of exercise and sleep. So if you were melancholic (cold and dry), you would want to heat foods that were hot and wet. Such a diet and regimen might also counteract your negative personality traits.

This system was elaborated even further. Each humor was associated with a different stage of life. Yellow bile dominated childhood, blood dominated youth and adolescence, phlegm dominated middle age, and black bile dominated old age. So whatever your natural balance of the humors, you would tend to have more yellow bile as a child and more black bile when you were elderly. This explained why personality traits often change over the course of a person’s life. The “hot-blooded” young person becomes a cooler and calmer middle-aged person. It also explained why people of different age groups were prone to different diseases.

Further, each humor was associated with a particular season. Black bile dominated in winter, phlegm in autumn, blood in spring, and yellow bile in summer. So whatever your natural constitution and whatever your stage of life, your humoral balance would shift over the course of a year. This explained why many diseases were more prevalent at certain times of the year.

Humors and temperaments were not just part of medical theory, they were part of art, literature, culture and everyday life in medieval and Renaissance Europe. To get a sense of their broad reach, check out the National Library of Medicine’s on-line Exhibit “And there’s the humor of it”: Shakespeare and the four humors. I pulled a number of images and useful references from this site.

III. RELIGION

As Greek and Islamic medicine was assimilated into the predominantly Christian culture of medieval Europe, it underwent some changes and adaptations. Christians believed disease was caused by sin, and religious leaders certainly urged people to pray for relief of their suffering, and to accept incurable pain or disease with patience and piety. However, religious responses to injury and disease were by no means incompatible with medical responses. Although Christians believed disease was a result of sin, they tended NOT to believe that an individual’s disease was a direct result of that individual’s sin. Rather they believed the fact that disease existed at all was the result of original sin. When God first created Adam and Eve, they were absolutely perfect physically, and in their original state of created perfection they would never have experienced disease or any other kind of suffering. When Adam and Eve bit into the forbidden fruit, they forever altered both their own nature and the entire natural world. The once perfect bodies of Adam and Eve became subject to disease, decay and death, as did the bodies of all their descendants. This idea is represented in the German artist Albrecht Dürer’s engraving of the Fall of Adam and Eve of 1504.

The artist captures the moment before the Fall, just before Adam and Eve bite into the forbidden fruit and lose Paradise forever. Four animals in the background represent each of the four humors. The cat symbolizes yellow bile, the elk black bile, the ox phlegm and the rabbit blood. Once Adam and Eve sin, these humors are thrown into disarray. That is, if Adam and Eve had never sinned, their humors would have remained in perfect balance forever. Because they did sin, they and all their descendants are subject to humoral imbalances, that is, diseases.

Religious leaders did not try to dissuade Christians from seeking medical treatment. In fact, several theologians argued that NOT seeking medical help when sick was tantamount to suicide, which was a sin. Christians generally believed that while God punished humankind with disease, He also provided the means for relief. The medicinal properties of various herbs, for example, were implanted by God. These medicinal virtues were signs of God’s Providence and His love for human beings. Thus, to refuse medicine was to deny God’s Providence. Finally, the study of human anatomy was believed to increase piety by demonstrating the beauty and wonder of the human body, the pinnacle of God’s creation. For these reasons, both religious and secular authorities encouraged the study of medicine and advised people to seek medical advice when they were sick.

ASSIGNMENT: In class we will take a closer look at death and disease in early modern London by examining a Bill of Mortality from 1665. Download and/or print out the following document:

For more information on the Bills of Mortality see Rebecca Onion’s blog post on Slate here, and browse Craig Spence’s blog on violent deaths in the Bills here (and especially his post About the Bills).

Here’s a better image of a Bill of Mortality for just one week in 1665.

Watch a lecture called Lotions and Potions: Medical Books from the Middle Ages by medievalist extraordinaire, Dr. Erik Kwakkel.